Artist David Budd, 1927-1991

Mike Solomon

Excerpted from the memoir, Our Salon by the Sea

© 2022 Mike Solomon

1975

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

1949

1950

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

David took in all of Syd’s advice. Syd told him he should go to New York as soon as he could to meet the most important artists of the day. David went in 1954 and did in fact meet his hero Jackson Pollock, as well as many of the other Abstract Expressionists. You can see something of his admiration for Pollock in his comments in the Jeffrey Potter book, To A Violent Grave: An Oral Biography of Jackson Pollock. I think his particular attraction to Pollock’s work, judging from all David said to me over the years, was the power that gestures made with paint had to create new structures, structures of the invisible worlds, maps of the energies of thought and emotion.

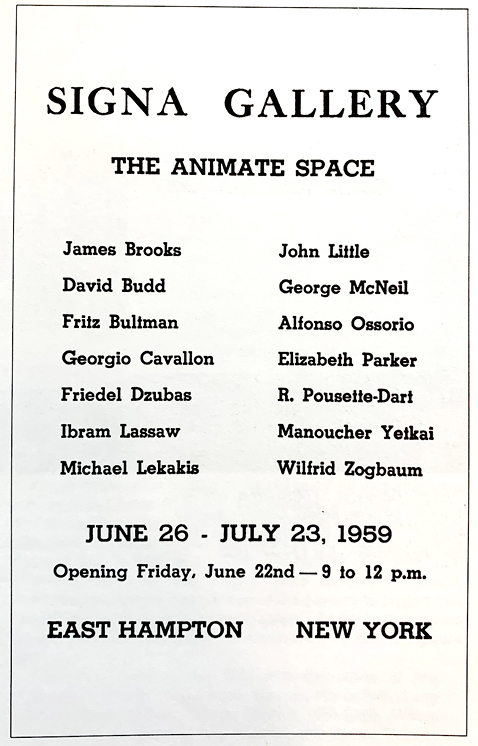

1959

Oil on Canvas

Studying gestural abstraction, tracking it, understanding artists’ mechanisms were a major occupation of many of the younger artists who venerated those who originated the genre. David and his peers went deep into everything Pollock, de Kooning, and Kline did. They were their triumvirate.

Sculptor John Chamberlain, one of David’s closest friends, once said to me, “Nobody thinks about how well Pollock knew viscosity. How he could make a line of paint go from here to there (hands outstretched) just using a stick.” Under Pollock’s influence, this aspect of viscosity became one of David’s main interests.

1949

1961

Oil on canvas

77 ½ x 38 in.

Photo courtesy of Mike Solomon

1958

Oil on canvas

67 ⅛ x 79 in.

Collection of Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, NY

c. 1950

Photo: Hans Namuth Estate

1959

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

1959

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

c. 1973

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

1978

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

The year I turned 15 was a milestone. It was the first year I started school in Sarasota rather than in East Hampton. Because we lived six months in each place, normally I would start the school year in the Hamptons in late August or early September and then be pulled out in November so my parents could go to Florida, their state of residence, to cast their votes. Every year in November I would try to take up studies again with new books and teachers in Florida. This pattern wreaked havoc on my academics, especially in math, in which each step of learning was contiguous and precise. That year, 1971, my parents felt I could go to Florida on my own to start school at the beginning of the school year. I lived alone in the Midnight Pass house on the beach with no supervision at all.

c. 1972

Photo: Alexander Georges

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

c. 1968

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

c. 1971

Photo: Syd Solomon

I was used to strolling into Syd’s studio anytime I liked. I watched him paint a lot and he never minded.

c. 1972

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

I think he even liked having me there, so I strolled into the studio while David was working, too, and then I’d stroll back out with my fifteen year old obliviousness securely intact. I did not see or feel the vibe, the neck hairs bristling, the darting eyes, and the frustration in the redness of his forehead at having his concentration disturbed until one morning about a week into my arrival. He was working away and again I sauntered in to see how he was doing. Then. . . Boom! He just exploded with a torrent of accusations about my insensitivity, my obliviousness, my taking for granted that it was my space, but, it was not mine to occupy based on the arrangement he had made. Oh, it was intense. While ranting, he’d stopped painting and came at me quickly so that I had to back out of the studio door I was about to enter and onto the bridge walkway that connected it to the house, normally a lovely space where everybody congregated during parties, but now the scene of an angry, almost physical confrontation. Finally, he began to calm down. The look on my face must have told him that not only was I extremely sorry but that I had no idea I had committed such an evil deed. I remember watching him gradually softening, trying to make the effort to adjust. The poor guy had been holding it back since I arrived and it just had to come out. Later, he said he was angrier with my parents than with me for leaving me without any resources at all for the summer.

1978

Photo: Mike Solomon

1978

Photo: Mike Solomon

1978

Photo: Mike Solomon

1980

Photo courtesy of Mike Solomon

From time to time that summer I would gingerly venture into the studio to watch David work or would look at finished paintings with him. The paintings then were done mostly in browns and blacks, like the water in the Gulf of Mexico when it’s stormy and mixed with sand. He had divined these color spectra, knowing it was symbolic of a kind of dark, surly, yet beautiful energy. The work Turtle Beach was painted then. It is one of the key works made that summer.

1972

Collection of Ringling College of Art and Design

Photo: Ryan Gamma

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

1972

Oil on canvas

60 x 60 in.

Courtesy of Ringling College of Art and Design

Photo: Ryan Gamma

When I wanted to watch him work I would bring a book to read into the studio so that my presence was not entirely focused on him. In the hours, sometimes reading, sometimes lifting my eyes from the pages to watch him, I observed how he worked his way across the canvas, the repetitions, dipping his palette knife into the color and then adding the strokes with a swishing noise. It was rhythmical. He held the palette knife like a conductor holds a baton, balanced between his thumb and forefinger. And it was like music, like writing and playing music at the same time, riff after riff after riff in seemingly endless repetition and improvisation.

Imagine yourself, if you can, painting one of his paintings, what it took physically to cover all that space, a huge expanse compared to the scale and stride of each mark. It was like walking or swimming, stroke after stroke. His series Journey Without Maps tell us that he saw his mark making as a kind of travel. One can get lost in his sea of waves, in his ripples, in the patterns. Surely David knew what it was to meditate, what the mystic trance was because he worked in that state, lost between breaths in and breaths out. When a painting was done, it was done, and there was no going back and “fixing” something. This is why he needed to be in such a special state of mind while he worked. The painting was going to happen only once, with no chance of revising it. It was a performance. Once I understood that, I felt even more honored to have been allowed to witness it first-hand.

Photo: Peter Bellamy

That’s about when he started the Silver Series, which contributed to him receiving the Guggenheim Award. He had worked with metallic tones from time to time before, and there are a number of beautiful pieces made with them, especially the big gold painting from 1980, Journey Without Maps XIII. It is perhaps one of his very best paintings. We had a talk about it once. He said using gold was a reference to the highest spiritual state, that using it was like “being in a spiritual landscape.” He knew I’d understand.

1980

78 x 126 in.

Oil on canvas

Photo courtesy of Mike Solomon

1986

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

1987

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

c. 1987

Photo courtesy of Solomon Archive

Excerpted from the memoir, Our Salon by the Sea

© 2022 Mike Solomon